Availability is the most important feature

— Mike Fisher, former CTO of Etsy

“I get knocked down, but I get up again…”

— Tubthumping, Chumbawumba

Every organization pays attention to resilience. The big question is

when.

Startups tend to only address resilience when their systems are already

down, often taking a very reactive approach. For a scaleup, excessive system

downtime represents a significant bottleneck to the organization, both from

the effort expended on restoring function and also from the impact of customer

dissatisfaction.

To move past this, resilience needs to be built into the business

objectives, which will influence the architecture, design, product

management, and even governance of business systems. In this article, we’ll

explore the Resilience and Observability Bottleneck: how you can recognize

it coming, how you might realize it has already arrived, and what you can do

to survive the bottleneck.

How did you get into the bottleneck?

One of the first goals of a startup is getting an initial product out

to market. Getting it in front of as many users as possible and receiving

feedback from them is typically the highest priority. If customers use

your product and see the unique value it delivers, your startup will carve

out market share and have a dependable revenue stream. However, getting

there often comes at a cost to the resilience of your product.

A startup may decide to skip automating recovery processes, because at

a small scale, the organization believes it can provide resilience through

the developers that know the system well. Incidents are handled in a

reactive nature, and resolutions come by hand. Possible solutions might be

spinning up another instance to handle increased load, or restarting a

service when it’s failing. Your first customers might even be aware of

your lack of true resilience as they experience system outages.

At one of our scaleup engagements, to get the system out to production

quickly, the client deprioritized health check mechanisms in the

cluster. The developers managed the startup process successfully for the

few times when it was necessary. For an important demo, it was decided to

spin up a new cluster so that there would be no externalities impacting

the system performance. Unfortunately, actively managing the status of all

the services running in the cluster was overlooked. The demo started

before the system was fully operational and an important component of the

system failed in front of prospective customers.

Fundamentally, your organization has made an explicit trade-off

prioritizing user-facing functionality over automating resilience,

gambling that the organization can recover from downtime through manual

intervention. The trade-off is likely acceptable as a startup while it’s

at a manageable scale. However, as you experience high growth rates and

transform from a

startup to a scaleup, the lack of resilience proves to be a scaling

bottleneck, manifesting as an increasing occurrence of service

interruptions translating into more work on the Ops side of the DevOps

team’s responsibilities, reducing the productivity of teams. The impact

seems to appear suddenly, because the effect tends to be non-linear

relative to the growth of the customer base. What was recently manageable

is suddenly extremely impactful. Eventually, the scale of the system

creates manual work beyond the capacity of your team, which bubbles up to

affect the customer experiences. The combination of reduced productivity

and customer dissatisfaction leads to a bottleneck that is hard to

survive.

The question then is, how do I know if my product is about to hit a

scaling bottleneck? And further, if I know about those signs, how can I

avoid or keep pace with my scale? That is what we’ll look to answer as we

describe common challenges we’ve experienced with our clients and the

solutions we have seen to be most effective.

Signs you are approaching a scaling bottleneck

It’s always difficult to operate in an environment in which the scale

of the business is changing rapidly. Investing in handling high traffic

volumes too early is a waste of resources. Investing too late means your

customers are already feeling the effects of the scaling bottleneck.

To shift your operating model from reactive to proactive, you have to

be able to predict future behavior with a confidence level sufficient to

support important business decisions. Making data driven decisions is

always the goal. The key is to find the leading indicators which will

guide you to prepare for, and hopefully avoid the bottleneck, rather than

react to a bottleneck that has already occurred. Based on our experience,

we have found a set of indicators related to the common preconditions as

you approach this bottleneck.

Resilience is not a first class consideration

This may be the least obvious sign, but is arguably the most important.

Resilience is thought of as purely a technical problem and not a feature

of the product. It’s deprioritized for new features and enhancements. In

some cases, it’s not even a concern to be prioritized.

Here’s a quick test. Listen in on the different discussions that

occur within your teams, and note the context in which resilience is

discussed. You may find that it isn’t included as part of a standup, but

it does make its way into a developer meeting. When the development team isn’t

responsible for operations, resilience is effectively siloed away.

In those cases, pay close attention to how resilience is discussed.

Evidence of inadequate focus on resilience is often indirect. At one

client, we’ve seen it come in the form of technical debt cards that not

only aren’t prioritized, but become a constant growing list. At another

client, the operations team had their backlog filled purely with

customer incidents, the majority of which dealt with the system either

not being up or being unable to process requests. When resilience concerns

are not part of a team’s backlog and roadmap, you’ll have evidence that

it is not core to the product.

Solving resilience by hand (reactive manual resilience)

How your organization resolve service outages can be a key indicator

of whether your product can scaleup effectively or not. The characteristics

we describe here are fundamentally caused by a

lack of automation, resulting in excessive manual effort. Are service

outages resolved via restarts by developers? Under high load, is there

coordination required to scale compute instances?

In general, we find

these approaches don’t follow sustainable operational practices and are

brittle solutions for the next system outage. They include bandaid solutions

which alleviate a symptom, but never truly solve it in a way that allows

for future resilience.

Ownership of systems are not well defined

When your organization is moving quickly, developing new services and

capabilities, quite often key pieces of the service ecosystem, or even

the infrastructure, can become “orphaned” – without clear responsibility

for operations. As a result, production issues may remain unnoticed until

customers react. When they do occur, it takes longer to troubleshoot which

causes delays in resolving outages. Resolution is delayed while ping ponging issues

between teams in an effort to find the responsible party, wasting

everyone’s time as the issue bounces from team to team.

This problem is not unique to microservice environments. At one

engagement, we witnessed similar situations with a monolith architecture

lacking clear ownership for parts of the system. In this case, clarity

of ownership issues stemmed from a lack of clear system boundaries in a

“ball of mud” monolith.

Ignoring the reality of distributed systems

Part of developing effective systems is being able to define and use

abstractions that enable us to simplify a complex system to the point

that it actually fits in the developer’s head. This allows developers to

make decisions about the future changes necessary to deliver new value

and functionality to the business. However, as in all things, one can go

too far, not realizing that these simplifications are actually

assumptions hiding critical constraints which impact the system.

Riffing off the fallacies of distributed computing:

- The network is not reliable.

- Your system is affected by the speed of light. Latency is never zero.

- Bandwidth is finite.

- The network is not inherently secure.

- Topology always changes, by design.

- The network and your systems are heterogeneous. Different systems behave

differently under load. - Your virtual machine will disappear when you least expect it, at exactly the

wrong time. - Because people have access to a keyboard and mouse, mistakes will

happen. - Your customers can (and will) take their next action in <

500ms.

Very often, testing environments provide perfect world

conditions, which avoids violating these assumptions. Systems which

don’t account for (and test for) these real-world properties are

designed for a world in which nothing bad ever happens. As a result,

your system will exhibit unanticipated and seemingly non-deterministic

behavior as the system starts to violate the hidden assumptions. This

translates into poor performance for customers, and incredibly difficult

troubleshooting processes.

Not planning for potential traffic

Estimating future traffic volume is difficult, and we find that we

are wrong more often than we are right. Over-estimating traffic means

the organization is wasting effort designing for a reality that doesn’t

exist. Under-estimating traffic could be even more catastrophic. Unexpected

high traffic loads could happen for a variety of reasons, and a social media marketing

campaign which unexpectedly goes viral is a good example. Suddenly your

system can’t manage the incoming traffic, components start to fall over,

and everything grinds to a halt.

As a startup, you’re always looking to attract new customers and gain

additional market share. How and when that manifests can be incredibly

difficult to predict. At the scale of the internet, anything could happen,

and you should assume that it will.

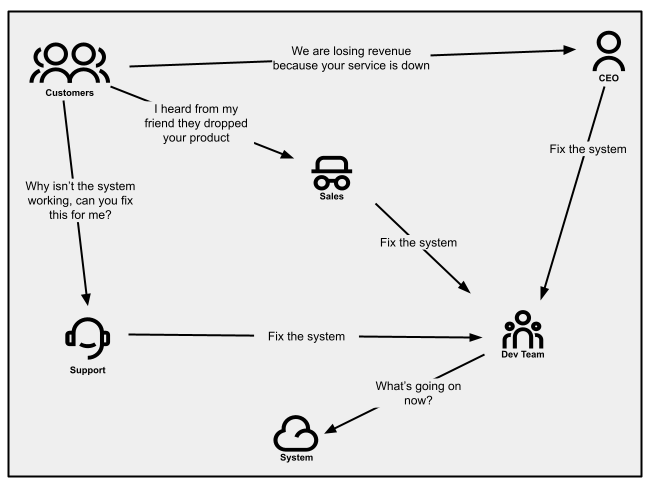

Alerted via customer notifications

When customers are invested in your product and believe the issue is

resolvable, they might try to contact your support staff for

help. That may be through email, calling in, or opening a support

ticket. Service failures cause spikes in call volume or email traffic.

Your sales people may even be relaying these messages because

(potential) customers are telling them as well. And if service outages

affect strategic customers, your CEO might tell you directly (this may be

okay early on, but it’s certainly not a state you want to be in long term).

Customer communications will not always be clear and straightforward, but

rather will be based on a customer’s unique experience. If customer success staff

do not realize that these are indications of resilience problems,

they will proceed with business as usual and your engineering staff will

not receive the feedback. When they aren’t identified and managed

correctly, notifications may then turn non-verbal. For example, you may

suddenly find the rate at which customers are canceling subscriptions

increases.

When working with a small customer base, knowing about a problem

through your customers is “mostly” manageable, as they are fairly

forgiving (they are on this journey with you after all). However, as

your customer base grows, notifications will begin to pile up towards

an unmanageable state.

Figure 1:

Communication patterns as seen in an organization where customer notifications

are not managed well.

How do you get out of the bottleneck?

Once you have an outage, you want to recover as quickly as possible and

understand in detail why it happened, so you can improve your system and

ensure it never happens again.

Tackling the resilience of your products and services while in the bottleneck

can be difficult. Tactical solutions often mean you end up stuck in fire after fire.

However if it’s managed strategically, even while in the bottleneck, not

only can you relieve the pressure on your teams, but you can learn from past recovery

efforts to help manage through the hypergrowth stage and beyond.

The following five sections are effectively strategies your organization can implement.

We believe they flow in order and should be taken as a whole. However, depending

on your organization’s maturity, you may decide to leverage a subset of

strategies. Within each, we lay out several solutions that work towards it’s

respective strategy.

Ensure you have implemented basic resilience techniques

There are some basic techniques, ranging from architecture to

organization, that can improve your resiliency. They keep your product

in the right place, enabling your organization to scale effectively.

Use multiple zones within a region

For highly critical services (and their data), configure and enable

them to run across multiple zones. This should give a bump to your

system availability, and increase your resiliency in the case of

disruption (within a zone).

Specify appropriate computing instance types and specifications

Business critical services should have computing capacity

appropriately assigned to them. If services are required to run 24/7,

your infrastructure should reflect those requirements.

Match investment to critical service tiers

Many organizations manage investment by identifying critical

service tiers, with the understanding that not all business systems

share the same importance in terms of delivering customer experience

and supporting revenue. Identifying service tiers and associated

resilience outcomes informed by service level agreements (SLAs), paired with architecture and

design patterns that support the outcomes, provides helpful guardrails

and governance for your product development teams.

Clearly define owners across your entire system

Each service that exists within your system should have

well-defined owners. This information can be used to help direct issues

to the right place, and to people who can effectively resolve them.

Implementing a developer portal which provides a software services

catalog with clearly defined team ownership helps with internal

communication patterns.

Automate manual resilience processes (within a timebox)

Certain resilience problems that have been solved by hand can be

automated: actions like restarting a service, adding new instances or

restoring database backups. Many actions are easily automated or simply

require a configuration change within your cloud service provider.

While in the bottleneck, implementing these capabilities can give the

team the relief it needs, providing much needed breathing room and

time to solve the root cause(s).

Make sure to keep these implementations at their simplest and

timeboxed (couple of days at max). Bear in mind these started out as

bandaids, and automating them is just another (albeit better) type of

bandaid. Integrate these into your monitoring solution, allowing you

to remain aware of how frequently your system is automatically recovering and how long it

takes. At the same time, these metrics allow you to prioritize

moving away from reliance on these bandaid solutions and make your

whole system more robust.

Improve mean time to restore with observability and monitoring

To work your way out of a bottleneck, you need to understand your

current state so you can make effective decisions about where to invest.

If you want to be 5 nines, but have no sense of how many nines are

actually currently provided, then it’s hard to even know what path you

should be taking.

To know where you are, you need to invest in observability.

Observability allows you to be more proactive in timing investment in

resilience before it becomes unmanageable.

Centralize your logs to be viewable through a single interface

Aggregate logs from core services and systems to be available

through a central interface. This will keep them accessible to

multiple eyes easily and reduce troubleshooting efforts (potentially

improving mean time to recovery).

Define a clear structured format for log messages

Anyone who’s had to parse through aggregated log messages can tell

you that when multiple services follow differing log structures it’s

an incredible mess to find anything. Every service just ends up

speaking its own language, and only the original authors understand

the logs. Ideally, once those logs are aggregated, anyone from

developers to support teams should be able to understand the logs, no

matter their origin.

Structure the log messages using an organization-wide standardized

format. Most logging tools support a JSON format as a standard, which

enables the log message structure to contain metadata like timestamp,

severity, service and/or correlation-id. And with log management

services (through an observability platform), one can filter and search across these

properties to help debug bottleneck issues. To help make search more

efficient, prefer fewer log messages with more fields containing

pertinent information over many messages with a small number of

fields. The actual messages themselves may still be unique to a

specific service, but the attributes associated with the log message

are helpful to everyone.

Treat your log messages as a key piece of information that is

visible to more than just the developers that wrote them. Your support team can

become more effective when debugging initial customer queries, because

they can understand the structure they are viewing. If every service

can speak the same language, the barrier to provide support and

debugging assistance is removed.

Add observability that’s close to your customer experience

What gets measured gets managed.

— Peter Drucker

Though infrastructure metrics and service message logs are

useful, they are fairly low level and don’t provide any context of

the actual customer experience. On the other hand, customer

notifications are a direct indication of an issue, but they are

usually anecdotal and don’t provide much in terms of pattern (unless

you put in the work to find one).

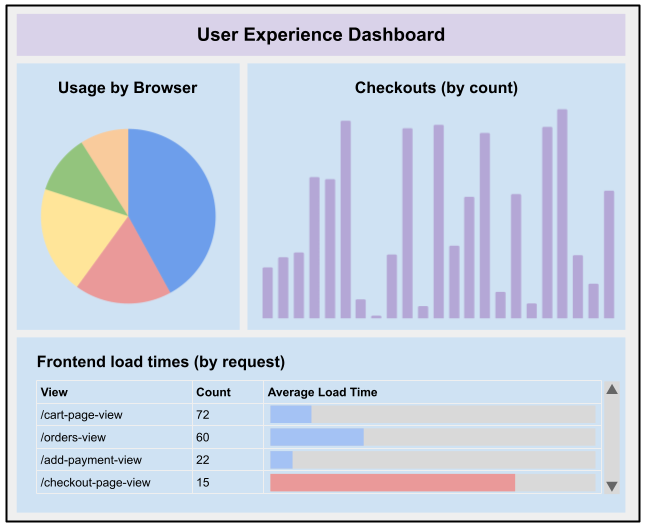

Monitoring core business metrics enables teams to observe a

customer’s experience. Typically defined through the product’s

requirements and features, they provide high level context around

many customer experiences. These are metrics like completed

transactions, start and stop rate of a video, API usage or response

time metrics. Implicit metrics are also useful in measuring a

customer’s experiences, like frontend load time or search response

time. It’s crucial to match what is being observed directly

to how a customer is experiencing your product. Also

important to note, metrics aligned to the customer experience become

even more important in a B2B environment, where you might not have

the volume of data points necessary to be aware of customer issues

when only measuring individual components of a system.

At one client, services started to publish domain events that

were related to the product experience: events like added to cart,

failed to add to cart, transaction completed, payment approved, etc.

These events could then be picked up by an observability platform (like

Splunk, ELK or Datadog) and displayed on a dashboard, categorized and

analyzed even further. Errors could be captured and categorized, allowing

better problem solving on errors related to unexpected customer

experience.

Figure 2:

Example of what a dashboard focusing on the user experience could look like

Data gathered through core business metrics can help you understand

not only what might be failing, but where your system thresholds are and

how it manages when it’s outside of that. This gives further insight into

how you might get through the bottleneck.

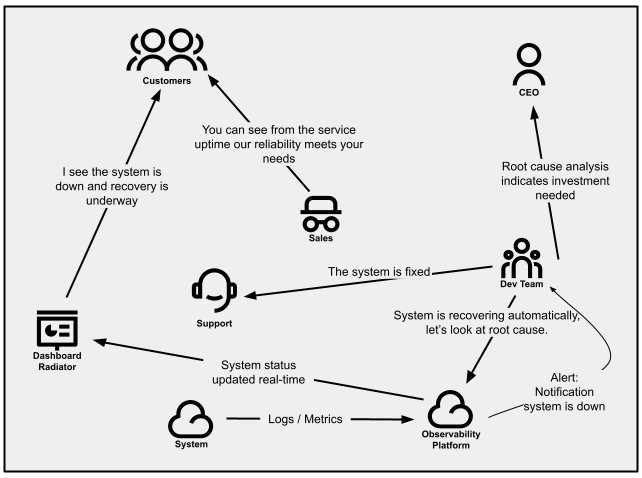

Provide product status insight to customers using status indicators

It can be difficult to manage incoming customer inquiries of

different issues they are facing, with support services quickly finding

they are fighting fire after fire. Managing issue volume can be crucial

to a startup’s success, but within the bottleneck, you need to look for

systemic ways of reducing that traffic. The ability to divert call

traffic away from support will give some breathing room and a better chance to

solve the right problem.

Service status indicators can provide customers the information they are

seeking without having to reach out to support. This could come in

the form of public dashboards, email messages, or even tweets. These can

leverage backend service health and readiness checks, or a combination

of metrics to determine service availability, degradation, and outages.

During times of incidents, status indicators can provide a way of updating

many customers at once about your product’s status.

Building trust with your customers is just as important as creating a

reliable and resilient service. Providing methods for customers to understand

the services’ status and expected resolution timeframe helps build

confidence through transparency, while also giving the support staff

the space to problem-solve.

Figure 3:

Communication patterns within an organization that proactively manages how customers are notified.

Shift to explicit resilience business requirements

As a startup, new features are often considered more valuable

than technical debt, including any work related to resilience. And as stated

before, this certainly made sense initially. New features and

enhancements help keep customers and bring in new ones. The work to

provide new capabilities should, in theory, lead to an increase in

revenue.

This doesn’t necessarily hold true as your organization

grows and discovers new challenges to increasing revenue. Failures of

resilience are one source of such challenges. To move beyond this, there

needs to be a shift in how you value the resilience of your product.

Understand the costs of service failure

For a startup, the consequences of not hitting a revenue target

this ‘quarter’ might be different than for a scaleup or a mature

product. But as often happens, the initial “new features are more

valuable than technical debt” decision becomes a permanent fixture in the

organizational culture – whether the actual revenue impact is provable

or not; or even calculated. An aspect of the maturity needed when

moving from startup to scaleup is in the data-driven element of

decision-making. Is the organization tracking the value of every new

feature shipped? And is the organization analyzing the operational

investments as contributing to new revenue rather than just a

cost-center? And are the costs of an outage or recurring outages known

both in terms of wasted internal labor hours as well as lost revenue?

As a startup, in most of these regards, you’ve got nothing to lose.

But this is not true as you grow.

Therefore, it’s important to start analyzing the costs of service

failures as part of your overall product management and revenue

recognition value stream. Understanding your revenue “velocity” will

provide an easy way to quantify the direct cost-per-minute of

downtime. Tracking the costs to the team for everyone involved in an

outage incident, from customer support calls to developers to management

to public relations/marketing and even to sales, can be an eye-opening experience.

Add on the opportunity costs of dealing with an outage rather than

expanding customer outreach or delivering new features and the true

scope and impact of failures in resilience become apparent.

Manage resilience as a feature

Start treating resilience as more than just a technical

expectation. It’s a core feature that customers will come to expect.

And because they expect it, it should become a first class

consideration among other features. Part of this evolution is about shifting where the

responsibility lies. Instead of it being purely a responsibility for

tech, it’s one for product and the business. Multiple layers within

the organization will need to consider resilience a priority. This

demonstrates that resilience gets the same amount of attention that

any other feature would get.

Close collaboration between

the product and technology is vital to make sure you’re able to

set the correct expectations across story definition, implementation

and communication to other parts of the organization. Resilience,

though a core feature, is still invisible to the customer (unlike new

features like additions to a UI or API). These two groups need to

collaborate to ensure resilience is prioritized appropriately and

implemented effectively.

The objective here is shifting resilience from being a reactionary

concern to a proactive one. And if your teams are able to be

proactive, you can also react more appropriately when something

significant is happening to your business.

Requirements should reflect realistic expectations

Knowing realistic expectations for resilience relative to

requirements and customer expectations is key to keeping your

engineering efforts cost effective. Different levels of resilience, as

measured by uptime and availability, have vastly different costs. The

cost difference between “three nines” and “four nines” of availability

(99.9% vs 99.99%) may be a factor of 10x.

It’s important to understand your customer requirements for each

business capability. Do you and your customers expect a 24x7x365

experience? Where are your customers

based? Are they local to a specific region or are they global?

Are they primarily consuming your service via mobile devices, or are

your customers integrated via your public API? For example, it is an

ineffective use of capital to provide 99.999% uptime on a service delivered via

mobile devices which only enjoy 99.9% uptime due to cell phone

reliability limits.

These are important questions to ask

when thinking about resilience, because you don’t want to pay for the

implementation of a level of resiliency that has no perceived customer

value. They also help to set and manage

expectations for the product being built, the team building and

maintaining it, the folks in your organization selling it and the

customers using it.

Feel out your problems first and avoid overengineering

If you’re solving resiliency problems by hand, your first instinct

might be to just automate it. Why not, right? Though it can help, it’s most

effective when the implementation is time-boxed to a very short period

(a couple of days at max). Spending more time will likely lead to

overengineering in an area that was actually just a symptom.

A large amount of time, energy and money will be invested into something that is

just another bandaid and most likely is not sustainable, or even worse,

causes its own set of second-order challenges.

Instead of going straight to a tactical solution, this is an

opportunity to really feel out your problem: Where do the fault lines

exist, what is your observability trying to tell you, and what design

choices correlate to these failures. You may be able to discover those

fault lines through stress, chaos or exploratory testing. Use this

opportunity to your advantage to discover other system stress points

and determine where you can get the largest value for your investment.

As your business grows and scales, it’s critical to re-evaluate

past decisions. What made sense during the startup phase may not get

you through the hypergrowth stages.

Leverage multiple techniques when gathering requirements

Gathering requirements for technically oriented features

can be difficult. Product managers or business analysts who are not

versed in the nomenclature of resilience can find it hard to

understand. This often translates into vague requirements like “Make x service

more resilient” or “100% uptime is our goal”. The requirements you define are as

important as the resulting implementations. There are many techniques

that can help us gather those requirements.

Try running a pre-mortem before writing requirements. In this

lightweight activity, individuals in different roles give their

perspectives about what they think could fail, or what is failing. A

pre-mortem provides valuable insights into how folks perceive

potential causes of failure, and the related costs. The ensuing

discussion helps prioritize things that need to be made resilient,

before any failure occurs. At a minimum, you can create new test

scenarios to further validate system resilience.

Another option is to write requirements alongside tech leads and

architecture SMEs. The responsibility to create an effective resilient system

is now shared amongst leaders on the team, and each can speak to

different aspects of the design.

These two techniques show that requirements gathering for

resilience features isn’t a single responsibility. It should be shared

across different roles within a team. Throughout every technique you

try, keep in mind who should be involved and the perspectives they bring.

Evolve your architecture and infrastructure to meet resiliency needs

For a startup, the design of the architecture is dictated by the

speed at which you can get to market. That often means the design that

worked at first can become a bottleneck in your transition to scaleup.

Your product’s resilience will ultimately come down to the technology

choices you make. It may mean examining your overall design and

architecture of the system and evolving it to meet the product

resilience needs. Much of what we spoke to earlier can help give you

data points and slack within the bottleneck. Within that space, you can

evolve the architecture and incorporate patterns that enable a truly

resilient product.

Broadly look at your architecture and determine appropriate trade-offs

Either implicitly or explicitly, when the initial architecture was

created, trade-offs were made. During the experimentation and gaining

traction phases of a startup, there is a high degree of focus on

getting something to market quickly, keeping development costs low,

and being able to easily modify or pivot product direction. The

trade-off is sacrificing the benefits of resilience

that would come from your ideal architecture.

Take an API backed by Functions as a Service (FaaS). This approach is a great way to

create something with little to no management of the infrastructure it

runs on, potentially ticking all three boxes of our focus area. On the

other hand, it’s limited based on the infrastructure it’s allowed to

run on, timing constraints of the service and the potential

communication complexity between many different functions. Though not

unachievable, the constraints of the architecture may make it

difficult or complex to achieve the resilience your product needs.

As the product and organization grows and matures, its constraints

also evolve. It’s important to acknowledge that early design decisions

may no longer be appropriate to the current operating environment, and

consequently new architectures and technologies need to be introduced.

If not addressed, the trade-offs made early on will only amplify the

bottleneck within the hypergrowth phase.

Enhance resilience with effective error recovery strategies

Data gathered from monitors can show where high failure

rates are coming from, be it third-party integrations, backed-up queues,

backoffs or others. This data can drive decisions on what are

appropriate recovery strategies to implement.

Use caching where appropriate

When retrieving information, caching strategies can help in two

ways. Primarily, they can be used to reduce the load on the service by

providing cached results for the same queries. Caching can also be

used as the fallback response when a backend service fails to return

successfully.

The trade-off is potentially serving stale data to customers, so

ensure that your use case is not sensitive to stale data. For example,

you wouldn’t want to use cached results for real-time stock price

queries.

Use default responses where appropriate

As an alternative to caching, which provides the last known

response for a query, it is possible to provide a static default value

when the backend service fails to return successfully. For example,

providing retail pricing as the fallback response for a pricing

discount service will do no harm if it is better to risk losing a sale

rather than risk losing money on a transaction.

Use retry strategies for mutation requests

Where a client is calling a service to effect a change in the data,

the use case may require a successful request before proceeding. In

this case, retrying the call may be appropriate in order to minimize

how often error management processes need to be employed.

There are some important trade-offs to consider. Retries without

delays risk causing a storm of requests which bring the whole system

down under the load. Using an exponential backoff delay mitigates the

risk of traffic load, but instead ties up connection sockets waiting

for a long-running request, which causes a different set of

failures.

Use idempotency to simplify error recovery

Clients implementing any type of retry strategy will potentially

generate multiple identical requests. Ensure the service can handle

multiple identical mutation requests, and can also handle resuming a

multi-step workflow from the point of failure.

Design business appropriate failure modes

In a system, failure is a given and your goal is to protect the end

user experience as much as possible. Specifically in cases that are

supported by downstream services, you may be able to anticipate

failures (through observability) and provide an alternative flow. Your

underlying services that leverage these integrations can be designed

with business appropriate failure modes.

Consider an ecommerce system supported by a microservice

architecture. Should downstream services supporting the ordering

function become overwhelmed, it would be more appropriate to

temporarily disable the order button and present a limited error

message to a customer. While this provides clear feedback to the user,

Product Managers concerned with sales conversions might instead allow

for orders to be captured and alert the customer to a delay in order

confirmation.

Failure modes should be embedded into upstream systems, so as to ensure

business continuity and customer satisfaction. Depending on your

architecture, this might involve your CDN or API gateway returning

cached responses if requests are overloading your subsystems. Or as

described above, your system might provide for an alternative path to

eventual consistency for specific failure modes. This is a far more

effective and customer focused approach than the presentation of a

generic error page that conveys ‘something has gone wrong’.

Resolve single points of failure

A single service can easily go from managing a single

responsibility of the product to multiple. For a startup, appending to

an existing service is often the simplest approach, as the

infrastructure and deployment path is already solved. However,

services can easily bloat and become a monolith, creating a point of

failure that can bring down many or all parts of the product. In cases

like this, you’ll need to understand ways to split up the architecture,

while also keeping the product as a whole functional.

At a fintech client, during a hyper-growth period, load

on their monolithic system would spike wildly. Due to the monolithic

nature, all of the functions were brought down simultaneously,

resulting in lost revenue and unhappy customers. The long-term

solution was to start splitting the monolith into several separate

services that could be scaled horizontally. In addition, they

introduced event queues, so transactions were never lost.

Implementing a microservice approach is not a simple and straightforward

task, and does take time and effort. Start by defining a domain that

requires a resiliency boost, and extract it’s capabilities piece by piece.

Roll out the new service, adjust infrastructure configuration as needed (increase

provisioned capacity, implement auto scaling, etc) and monitor it.

Ensure that the user journey hasn’t been affected, and resilience as

a whole has improved. Once stability is achieved, continue to iterate over

each capability in the domain. As noted in the client example, this is

also an opportunity to introduce architectural elements that help increase

the general resilience of your system. Event queues, circuit breakers, bulkheads and

anti-corruption layers are all useful architectural components that

increase the overall reliability of the system.

Continually optimize your resilience

It’s one thing to get through the bottleneck, it’s another to stay

out of it. As you grow, your system resiliency will be continually

tested. New features result in new pathways for increased system load.

Architectural changes introduces unknown system stability. Your

organization will need to stay ahead of what will eventually come. As it

matures and grows, so should your investment into resilience.

Regularly chaos test to validate system resilience

Chaos engineering is the bedrock of truly resilient products. The

core value is the ability to generate failure in ways that you might

never think of. And while that chaos is creating failures, running

through user scenarios at the same time helps to understand the user

experience. This can provide confidence that your system can withstand

unexpected chaos. At the same time, it identifies which user

experiences are impacted by system failures, giving context on what to

improve next.

Though you may feel more comfortable testing against a dev or QA

environment, the value of chaos testing comes from production or

production-like environments. The goal is to understand how resilient

the system is in the face of chaos. Early environments are (usually)

not provisioned with the same configurations found in production, thus

will not provide the confidence needed. Running a test like

this in production can be daunting, so make sure you have confidence in

your ability to restore service. This means the entire system can be

spun back up and data can be restored if needed, all through automation.

Start with small understandable scenarios that can give useful data.

As you gain experience and confidence, consider using your load/performance

tests to simulate users while you execute your chaos testing. Ensure teams and

stakeholders are aware that an experiment is about to be run, so they

are prepared to monitor (in case things go wrong). Frameworks like

Litmus or Gremlin can provide structure to chaos engineering. As

confidence and maturity in your resilience grows, you can start to run

experiments where teams are not alerted beforehand.

Recruit specialists with knowledge of resilience at scale

Hiring generalists when building and delivering an initial product

makes sense. Time and money are incredibly valuable, so having

generalists provides the flexibility to ensure you can get out to

market quickly and not eat away at the initial investment. However,

the teams have taken on more than they can handle and as your product

scales, what was once good enough is no longer the case. A slightly

unstable system that made it to market will continue to get more

unstable as you scale, because the skills required to manage it have

overtaken the skills of the existing team. In the same vein as

technical

debt,

this can be a slippery slope and if not addressed, the problem will

continue to compound.

To sustain the resilience of your product, you’ll need to recruit

for that expertise to focus on that capability. Experts bring in a

fresh view on the system in place, along with their ability to

identify gaps and areas for improvement. Their past experiences can

have a two-fold effect on the team, providing much needed guidance in

areas that sorely need it, and a further investment in the growth of

your employees.

Always maintain or improve your reliability

In 2021, the State of Devops report expanded the fifth key metric from availability to reliability.

Under operational performance, it asserts a product’s ability to

retain its promises. Resilience ties directly into this, as it’s a

key business capability that can ensure your reliability.

With many organizations pushing more frequently to production,

there needs to be assurances that reliability remains the same or gets better.

With your observability and monitoring in place, ensure what it

tells you matches what your service level objectives (SLOs) state. With every deployment to

production, the monitors should not deviate from what your SLAs

guarantee. Certain deployment structures, like blue/green or canary

(to some extent), can help to validate the changes before being

released to a wide audience. Running tests effectively in production

can increase confidence that your agreements haven’t swayed and

resilience has remained the same or better.

Resilience and observability as your organization grows

Phase 1

Experimenting

Prototype solutions, with hyper focus on getting a product to market quickly

Phase 2

Getting Traction

Resilience and observability are manually implemented via developer intervention

Prioritization for solving resilience mainly comes from technical debt

Dashboards reflect low level services statistics like CPU and RAM

Majority of support issues come in via calls or text messages from customers

Phase 3

(Hyper) Growth

Resilience is a core feature delivered to customers, prioritized in the same vein as features

Observability is able to reflect the overall customer experience, reflected through dashboards and monitoring

Re-architect or recreate problematic services, improving the resilience in the process

Phase 4

Optimizing

Platforms evolve from internal facing services, productizing observability and compute environments

Run periodic chaos engineering exercises, with little to no notice

Augment teams with engineers that are versed in resilience at scale

Summary

As a scaleup, what determines your ability to effectively navigate the

hyper(growth) phase is in part tied to the resilience of your

product. The high growth rate starts to put pressure on a system that was

developed during the startup phase, and failure to address the resilience of

that system often results in a bottleneck.

To minimize risk, resilience needs to be treated as a first-class citizen.

The details may vary according to your context, but at a high level the

following considerations can be effective:

- Resilience is a key feature of your product. It is no longer just a

technical detail, but a key component that your customers will come to expect,

shifting the company towards a proactive approach. - Build customer status indicators to help divert some support requests,

allowing breathing room for your team to solve the important problems. - The customer experience should be reflected within your observability stack.

Monitor core business metrics that reflect experiences your customers have. - Understand what your dashboards and monitors are telling you, to get a sense

of what are the most critical areas to solve. - Evolve your architecture to meet your resiliency goals as you identify

specific challenges. Initial designs may work at small scale but become

increasingly limiting as you transition to a scaleup. - When architecting failure modes, find ways to fail that are friendly to the

consumer, helping to ensure continuity and customer satisfaction. - Define realistic resilience expectations for your product, and understand the

limitations with which it’s being served. Use this knowledge to provide your

customers with effective SLAs and reasonable SLOs. - Optimize your resilience when you’re through the bottleneck. Make chaos

engineering part of a regular practice or recruiting specialists.

Successfully incorporating these practices results in a future organization

where resilience is built into business objectives, across all dimensions of

people, process, and technology.