Microsoft and Procter & Gamble executives in early November offered detailed updates on how they will attempt to replenish fragile watersheds impacted by their water consumption.

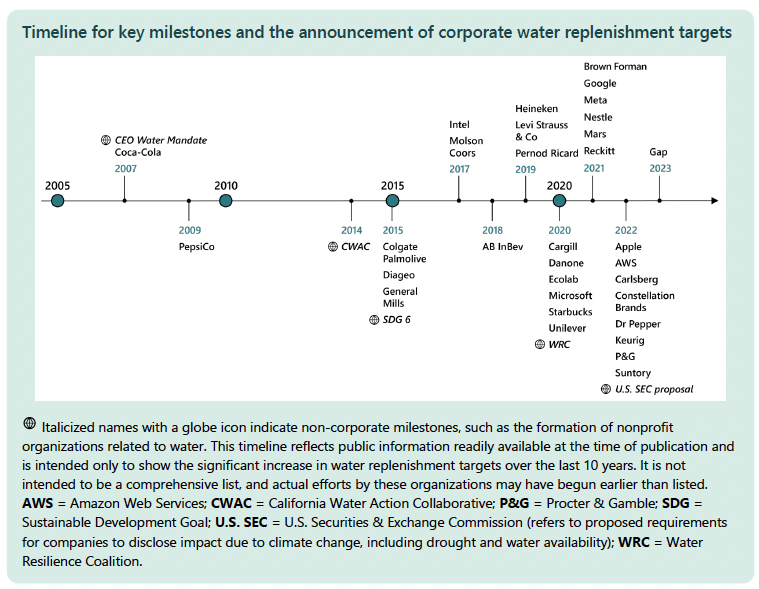

The pair are among a small but growing group of companies that have committed to restoring some or all of the water consumed in their manufacturing, agricultural, heating, cooling and other operational processes. The efforts are often combined with goals for efficiency and reuse, to reduce consumption.

Clean, drinkable water for food and manufacturing underpins an estimated $58 trillion in economic activity, the WWF estimates. But since 1970, one-third of the world’s wetlands have been lost and freshwater wildlife has declined by 83 percent, as rivers, lakes and aquifers disappear. Not enough companies are taking action quickly enough, according to an analysis of 72 companies from water-intensive industries by investor nonprofit Ceres. Just 13 percent of those businesses have time-bound goals to restore freshwater ecosystems, the report found.

A focus on consumption, not usage

P&G’s restoration goals identify 18 “water-stressed” regions globally, where it seeks to restore more water than its manufacturing consumes. It has also declared plans specific to Los Angeles and Mexico City to restore more water than is consumed during the use of its products, such as Cascade dishwasher detergent, Tide laundry soap, Crest toothpaste and Mr. Clean cleansers.

The word “consumed” is intentional: both P&G and Microsoft evaluated not just withdrawals, but also water that remains in finished goods and what evaporates during operations. They also closely examine where water is actually sourced.

As of early November, P&G had picked 23 projects in Arizona, California, Idaho and Utah to address its targets, P&G CSO Virginie Helias told me. The actions range from creek rechanneling to native habitat restoration to residential toilet leak detection. “There is a bit of a leap of faith in selecting projects,” said Helias. “That’s why it’s so important to have credible partners who have been doing this a long time.”

P&G estimates it will need to restore 48 billion liters to meet its targets. About 5 billion of that is related to manufacturing. Shannon Quinn, the company’s global water stewardship leader, said she is “satisfied” with P&G’s progress in some regions, including the U.S., and “anxious” to move faster in others where few projects exist today.

Microsoft’s “water positive” commitment, announced in September 2020, includes a broader goal to “replenish more water than it consumes on a global basis” from its direct operations. (It doesn’t include water from energy generation or its supply chain.) As of July, its restoration portfolio included 49 projects. In aggregate, they offer 61 billion liters of “potential volumetric water benefits.” That’s the equivalent of 24,000 Olympic swimming pools, the company said in a 38-page update in early November.

The tools for measuring impact are under development

Both P&G and Microsoft are working with the World Resources Institute on which portions of water basins should be prioritized, and how projects are selected and measured. Microsoft is relying on an approach called Volumetric Water Benefits Accounting, a way of calculating the benefits that can be claimed for a project. That framework is due for an update in the near future.

It’s not just about quantity. “Replenishment isn’t just about counting drops, it’s about basin health,” said Roberts. For example, there may also be co-benefits such as biodiversity or greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

P&G worked closely with WRI to create a methodology to assess risks, identify priority water basins and calculate the percentage of water it consumes. It published a 36-page analysis, including best practices and the formulas it uses to calculate metrics, in May.

Another resource both companies are watching is the freshwater hub developed by the Science Based Targets Network. It’s part of an effort to help corporations develop strategies for addressing nature and biodiversity.

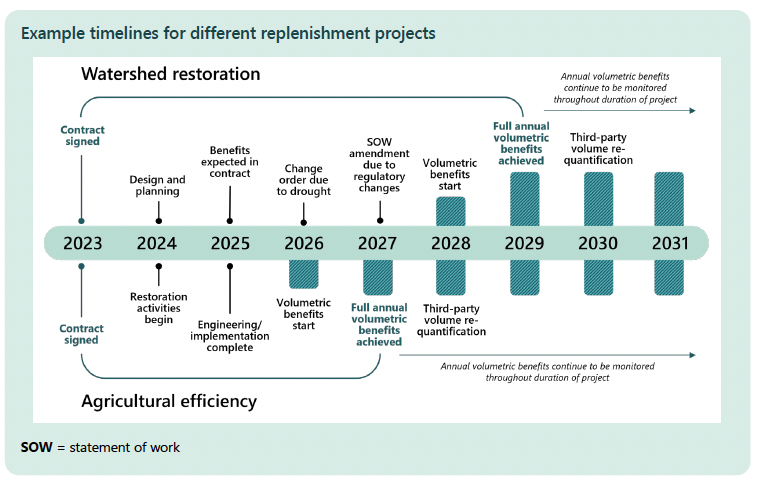

It takes time for watershed restoration projects to yield benefits

Both Microsoft and P&G expect to spend months, if not years, building their portfolios of water replenishment projects. It can take six to seven months to negotiate new relationships — and that’s in regions such as North America, where restoration activities are more advanced, Quinn said. “In other jurisdictions, it can take years.”

“Every year we are building up our base,” Roberts said. “Companies should not expect to jump in in 2028 and expect to get this done.”

Partnerships with NGOs and other corporations are a must

Many projects will also mean many partners. In the U.S., a key ally for Microsoft and P&G is Bonneville Environmental Foundation (BEF), which has played matchmaker for many projects. It has helped pull in multiple corporate investors to get work started more quickly. “Through intermediaries, they will know the others that are working in the watershed,” Quinn said. Other up-and-coming implementation partners include the California Water Action Collaborative and Agua Capital in Latin America.

Looking at leak detection

Corporations can get credit for replenishment in many ways, including efforts to remediate leaks in water infrastructure. An estimated 30 percent of the world’s piped water is lost before it reaches customers, according to the World Bank. Both Microsoft and P&G are backing the installation of leak detection devices from Sensor Industries in Los Angeles and, more recently, in Phoenix.

“Leak detection can lead to the reduction of water use, which can reduce stress on water resources in the region,” Quinn said. Each sensor can deliver an estimated 5,000 gallons of saved water, according to P&G’s estimates. The company has funded about 600 of them in Los Angeles.

Microsoft is financing projects in London, Phoenix and Mexico to deploy sensors from Fido Tech that use artificial intelligence and acoustics to identify leaks in municipal water. It’s one way to have an impact in the short term, Roberts said.

The work spans both rural and urban initiatives

Another piece of advice: Restoration portfolios should consider projects across the entire watershed. That means both rural initiatives, such as those focused on agriculture, and those in urban settings, such as blue-green roof projects that reduce stormwater runoff. “You need to understand where the water is coming from, exactly where, before you can understand where you need to go,” Quinn said.