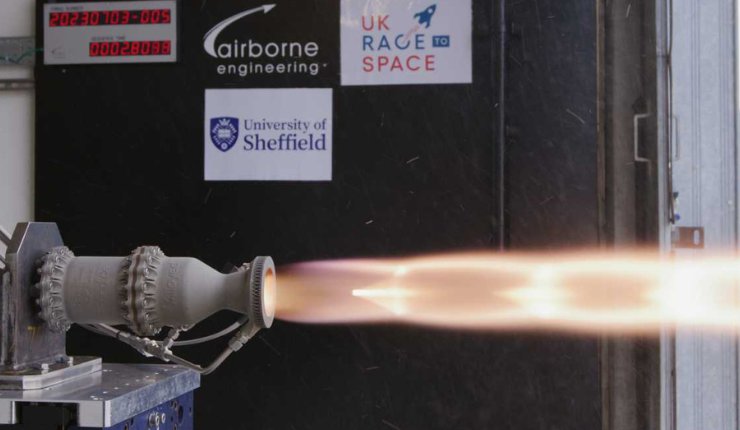

In July 2023, students at the University of Sheffield broke a record. A liquid rocket engine, similar to the kind used by SpaceX, was built under the Sunride Project and successfully fired as part of the Race to Space initiative. What was special about this one? It is believed to be the first metallic 3D printed rocket engine to be built and successfully tested by students in the UK.

The ‘SunFire’ engine, which the Sunride team says is the most powerful studentbuilt engine of its kind, uses both fuel and an oxidiser rather than breathing in oxygen like a jet engine. The engine is also regeneratively cooled, which means it uses fuel to cool the combustion chamber before it is burnt, which increases efficiency and saves weight.

The Sunride team says that the University of Sheffield’s Royce Discovery Centre, a research facility developing next-generation materials to meet UK manufacturing needs, was ‘instrumental’ in trialling the laser powder bed fusion metallic 3D printing that was used to build the engine. The engine was machined after printing by the university’s Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC) and Faculty of Engineering.

Henry Saunders, who served as a Design Engineer on Project Sunride, and is now studying for a PhD in additive manufacturing at the university, told TCT: “I got into metal additive manufacturing through wanting to build this engine. I reached out to a professor who I knew had some metal 3D printers at the uni, Iain Todd, who I ended up doing my PhD with. That project started with the aim of building the first student-built, regeneratively cooled liquid rocket engine in the UK. I went about trying to get other masters students to do other areas of the project, so we recruited people to come in alongside us and do other areas of the rocket engine design such as the CFD for cooling channels, combustion stability design as well, so we had academic help for their final year projects.”

Speaking to TCT about pursuing a PhD in additive manufacturing, Saunders added: “I had a job offer from a company called Alloyed, and then I had a PhD offer as well, and I just felt like there was so much more I could learn with additive, and the facilities at Sheffield are really good to get hands-on experience. There’s Aconity3D machines, Renishaws and some DED systems as well. There’s lots to play around with and it’s a really cool environment to be in.”

The engine was built by Saunders and his peers over a period of two years outside of their studies as part of the University of Sheffield’s Space Initiative, a programme to help STEM students use their skills to tackle some of the biggest problems in the industry after graduation. The rocket was then fired as part of the Race to Space initiative, which involved eight other teams, seven of which had rockets that were successfully fired.

The Race to Space initiative, which was launched by Dr. Alistair John, Deputy Director of Aerospace Engineering at The University of Sheffield alongside Saunders, aims to provide students with practical experiences solving engineering problems, through hands-on experience of designing, manufacturing and testing rocket engines. According to the initiative’s website, it is building a “UK-wide space training infrastructure”, as well as addressing diversity issues such as a lack of opportunities for women, ethnic minorities, and those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Dana Arabiyat, currently at Rolls-Royce, but who previously worked as a Design Engineer on Project Sunride and later Project Manager, told TCT: “We’ve been building rockets for a few years in Project Sunride, and to touch on propulsion was a very important step to increase a student’s knowledge and experience and get them ready for the space industry in the UK. We thought graduates in the UK lacked that practical knowledge, and we only learned rocket theory in university. We thought to have students get hands-on experience in building an actual liquid rocket engine would be invaluable, it will make us all stand out. Many people in the industry still haven’t experienced what we have working on this engine at the university. You can tell from how well our students are doing now in their careers, that we do have an advantage, we gave them the knowledge they need to excel in their career. I’m currently at Rolls-Royce, and I’m going to start working in combustion, the fact that I’ve done my masters dissertation on a liquid rocket engine combustion chamber gives me the edge.”

Dr. Alistair John added: “The space sector needs more highly skilled graduates. So we need to expose our students to practical engineering. Lots of aerospace degrees are pretty good on the theoretical side, but they get a limited experience of actually building and testing something real. So, to be able to go and actually test the rocket engine, make mistakes, test the rocket, actually fire it and see what happens, then iterate is a fantastic experience, and it’s really what this country needs more of. On top of that, it is expensive, but if you can find the funding and support, that’s obviously important, but what it does is give them the ability to really dream big.”

TCT asked both Arabiyat and Saunders what the moment was like when they got to successfully fire the SunFire engine on the first attempt. Arabiyat said: “Just the other day I was with a group of friends and I was asked: ‘If you could relive a moment in your life, what would it be?’ For me, it would be the moment I actually saw the flames coming out of the rocket, like I can’t believe it actually worked. It’s a moment I really want to re-live on repeat. We were being told: ‘Don’t worry if it doesn’t work’, and they just kept telling us not to expect much from the first try. It was two years of hard work waiting for this moment. We were all just looking at each other like, we did it, we actually did it.”

Saunders answered: “It was interesting actually, because I was due to be on a flight. We were in Oxford, and I had a flight from Gatwick that evening to go and do an experiment in France the following week. So, I was on quite a tight schedule to get it done, then it worked first time. It was unbelievable really. There’s a video of us from the bunker, we had to be in a control bunker, and so we were filming the screens, and we’re just swearing and going crazy. I was quite shocked the way it turned out.”

3D printing proved beneficial in bringing the design of the SunFire engine to life, as it allowed for the manufacture of small pipes for the cooling channels, integrated into the wall of the combustion chamber. Regeneratively cooling engines have been manufactured without 3D printing, but according to Dr. Alistair John, the cooling channels were ‘brazed on’ to the combustion chamber, whereas with a completely 3D printed rocket engine, the channels could be integrated and part of the design of the overall engine.

The SunFire engine had to be printed in two parts because of the height, and sealed together with a gasket. Dr. John told TCT that the team had worries that the engine would leak fluid, or fire would come out of the side, but the sealing technique worked.

Summing up her experience on the project, Arabiyat told TCT: “This has been a record-breaking competition where we had seven out of eight teams successfully get amazing flames out of their engines with the shock diamonds, it was just incredible what we managed to achieve. An incredible journey of learning, failing and reiterating, and project hand over as well, which is a very good skill. A lot of times you get started with something and then when these people graduate the project dies out. From design to test, the SunFire engine took two years to complete, so handing over to the next masters students, passing on the knowledge was a very important part of the process.”

The SunFire engine was fire tested at Airborne Engineering at the Westcott Space Cluster and 3D printed at the Satellite Applications Catapult. The Race to Space initiative is also believed to have set an unofficial world record itself, for the highest number of different hybrid/liquid rocket engines hot-fired for the first time on one site in one week.

Arabiyat also participated in another record-breaking launch as part of the SunRide Project in 2019, when a team of students fired a rocket 36,274ft into the sky, beating the previous UK record, which stood for 19 years, by almost 2,000ft. This rocket was named Helen in honour of The University of Sheffield’s Dr. Helen Sharman OBE, the first Briton in space.